About the Betty Jayne

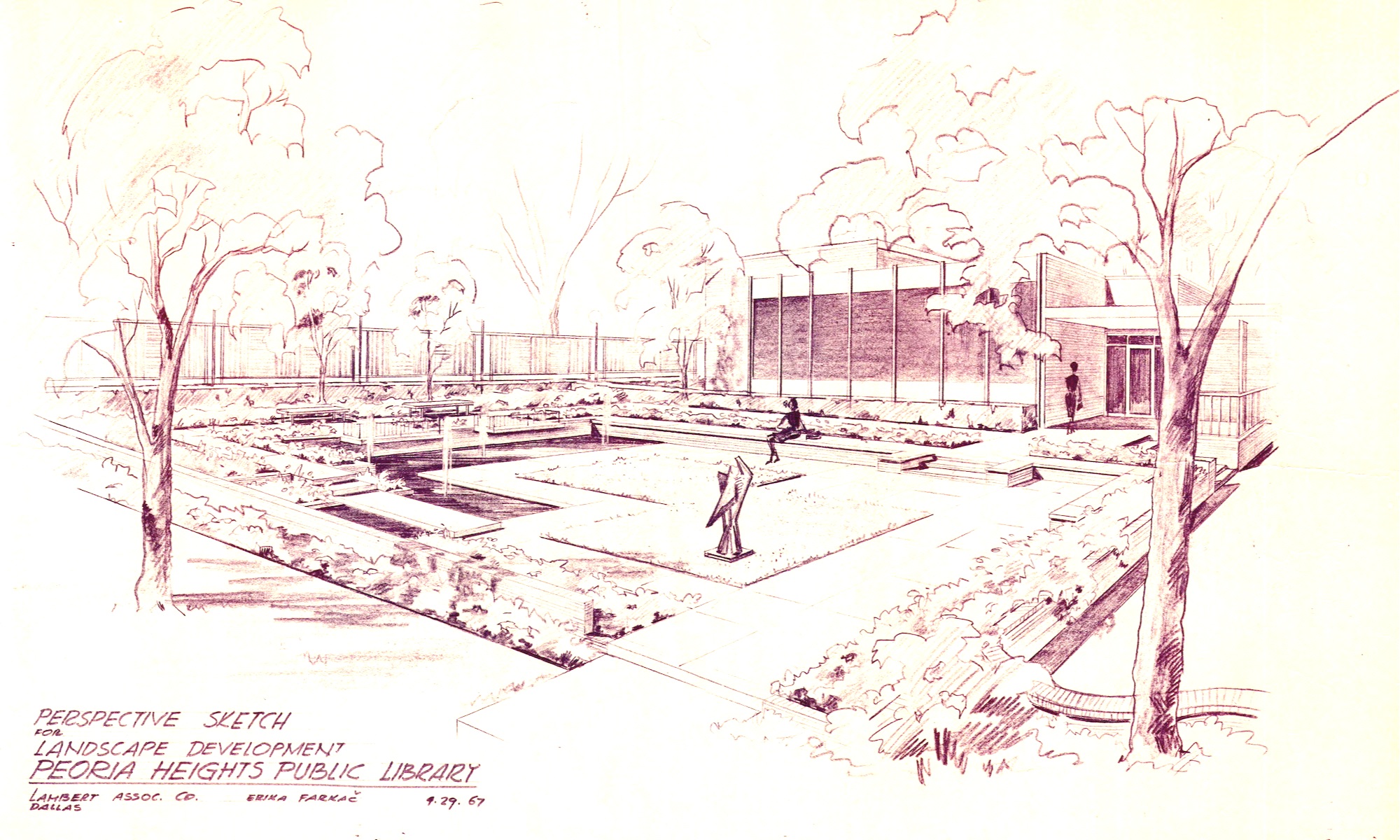

The Betty Jayne Brimmer Center for the Performing Arts began its story as the Peoria Heights Library. The library was established in 1936 and was open for 64 years. In 2019, Kim Blickenstaff purchased the property and converted it into what is now a leading art center in Peoria Heights. The purchase and renovation of the library were driven by Kim’s love of architecture, history, and all things Richard Doyle. Doyle’s sleek, modern style was preserved through the renovation, but the team did get creative when reimagining the building. The LP record shelves were repurposed into beautiful display shelves behind the Betty Jayne bar. Another notable change was the addition of the “Nanawall.” The original windows on the front elevation of the Library were removed and replaced with a wall of windows that can be opened to the front lawn. This “Nanawall” has changed the atmosphere and versatility of the building in ways Doyle could have never imagined, Today, the Betty houses a plethora of events: live music, dancing, special events and more!

Meet Betty Jayne Brimmer

Our venue’s namesake and renowned performer in her own time, Betty Jayne Brimmer would be proud to see what is happening inside these walls.

“My mom kept a scrapbook that she never told us about,” Blickenstaff explains. “I was going through my brother’s stuff after he passed away, and out comes this fragile, green scrapbook with every performance of my mom’s, from the time she was about 13 all the way through her career.” - Kim Blickenstaff, Founder & Chairman of KDB Group

Originally published in Peoriamagazines.com

Born in 1919, Betty Jayne Brimmer grew up in the waning days of Peoria’s much-vaunted vaudeville scene. Through an assemblage of photographs, playbills, programs, letters, ticket stubs and news clippings, her newly-discovered scrapbook details her life as a dancer in the Big Band Era. She performed at the Orpheum and other long-gone Peoria theaters; took the stage at banquet halls, country clubs, parks and schools; and was acclaimed as one of the finest acrobatic dancers in the country. Her “big break” came in the form of a newspaper ad: a national touring duo seeking an “acrobatically inclined young lady” to join their performance troupe.

Betty and Benny Fox billed themselves as “Sky Dancers: The World's Greatest Aerial Sensation.” Their act involved dancing on a tiny platform at the end of a long pole—doing the jitterbug and the Charleston hundreds of feet high in the air—and no net beneath them. On September 16, 1937, some 200,000 people congregated downtown to witness their daring performance, according to the Journal-Transcript, who called it “the largest crowd ever assembled in Peoria.” Among them was a young Betty Jayne Brimmer, fresh out of Peoria High School.

Soon she would go on the road with Betty and Benny Fox, performing all over the Midwest, into the Southwest and beyond. But fate would intervene in the form of marriage and the post-war arrival of five children—and her dancing career was cut short. But decades later, her name has acquired fresh prominence adorning a new arts venue in Peoria Heights.

The Betty Jayne Brimmer Center for the Performing Arts was the first of Kim Blickenstaff’s development projects to be announced. The community center and event space is notable for emphasizing the performing arts and arts education—a fitting tribute to his mother’s pre-marriage career. But she wasn’t the only performer in the family. His father Wyvern was a piano player, brother Scott played guitar, and brother Jon “could pick up any instrument and play it,” Blickenstaff recalls. “My sister danced, too. [My parents] made us all take lessons—that's where it all came from.”

A passion for the arts came early and naturally to the Blickenstaff clan. “We’d eat dinner, and Dad would sit at the piano and I’d sit down at the drums and play the brushes,” he notes. “When we got home from school, Jon and I would crank up the amplifier… He played guitar. I'll never forget hearing ‘Oh, Pretty Woman’ for the first time—I thought my brother wrote it!” he laughs. “And then I heard it on the radio and [realized] it’s Roy Orbison.”

These creative connections were passed down to the next generation as well. “My son Paul is like my brother Jon—he can play anything he picks up,” Blickenstaff explains. “My other son is very into architecture... and my daughter is a fashion designer in New York City.”

On a recent visit to Peoria Players Theatre, he found himself taking note of another striking family resemblance. “Randee is my brother Jon’s daughter—she’s into dance and acting. I saw her in A Chorus Line, and I swear it was like watching my mom when she was 22. She can do the same high kicks and splits... She’s very talented.”

Professional publicity shot of Betty Jayne Brimmer, photographed by Hollywood photographer Maurice Seymor.

Portrait by Maurice Seymour, a Chicago-based photographer who captured images of top dancers, stage and film stars from the 1920s through the 1960s.

Brimmer performs at a variety show presented by the Caterpillar Employees' Men's Glee Club.

Meet Richard L. Doyle (RLD)

By Mike Bailey

Originally published in Peoria Magazines’ iBi March 2019 Issue

The forward-thinking architect behind the Betty Jayne found a place to spread his wings in Peoria Heights.

In 2007, the Village of Peoria Heights hosted a festival to pay tribute to the two men who more than anyone else had “planted the seeds for modern-day Peoria Heights,” according to a Journal Star story at the time. Richard Doyle and Bill Rutherford, the architect and the philanthropist, both had died the year before just months apart, at ages 87 and 91, respectively.

They were contemporaries, similarly driven characters of stubborn temperament and demanding expectations, creative vision, and uncommon civic-mindedness and resolve. They were often collaborators and sometimes competitors, who somehow collided and cooperated in the same place and time to produce the Peoria Heights that has proved irresistible to another who has come along, influenced deeply by both.

That would be Kim Blickenstaff, the California businessman and central Illinois native who has come back home to build upon what they started.

Road to the Heights

Doyle and Rutherford are forever linked by the most prominent landmark in Peoria Heights, Tower Park, over which they did not see eye to eye—not least of all regarding the giant woodpecker doomed to peck at its exterior for eternity. Doyle also designed the headquarters for Rutherford’s Forest Park Foundation, over which they presumably found more consensus. In the end, there’s no disputing both men’s contribution to the Heights’ distinct look and feel, from its Prospect Road downtown to its Village Hall to its Congregational Church. And to think, it might not have been.

Indeed, the first love of the man who would design such iconic structures as Bradley University’s Robertson Memorial Field House was music, says his daughter, Dr. Mary Agnes “Maggie” Doyle, who worked side by side with her father before embarking upon a theater and teaching career in the Chicago area.

“Before World War II, he was a band leader and composer” who could play every instrument but percussion, Maggie explains. He was barely a teenager when from his Wheaton hometown he found himself the frontman for Dickie Doyle and the Melody Masters, playing dance halls all over the Midwest. Then he enlisted in the service as an officer in 1939, becoming the band leader of the Air Force Army Band, 98th Infantry Division.

But when he came back from occupied Japan in 1948, “the Swing and Big Band era was over,” says Maggie. Dick Doyle had to find another line of work.

The GI Bill allowed him to attend the University of Illinois to study architecture and structural engineering. Those might seem like incompatible careers, but it makes perfect sense, really. “He was a math wizard. His idea of a good, relaxing time was solving a math problem,” Maggie notes. “It informed both his music and his architecture. Building was a mathematical puzzle to be solved.”

Mid-Century Modern

It’s also why he would be so pleased to see his favorite building, the Heights’ former Kelly Avenue Library, repurposed into a performing arts center that marries both of his career paths. The Betty Jayne Brimmer Center for the Performing Arts was named in honor of the former Big Band-era dancer, who was Kim Blickenstaff’s mother. You could say there’s a certain symbiosis at work here.

“Days before he passed, he talked about buying back the library. It was a very modern design for the Heights” and he was “keen on it being a kind of civic center,” says Maggie, who grew up on Prospect Lane with her family.

Blickenstaff looks at the former library and the Doyle-designed Prospect Mall facility, destined for a boutique hotel, and sees “a blend of Bauhaus and Frank Lloyd Wright.” Maggie Doyle calls it “mid-century modern,” practiced and popularized by the likes of architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in Chicago.

Its clean and simple lines, its bountiful use of windows to bring the outside in, its open floor plans, its emphasis on function as the equal of form, its integration with the natural environment surrounding it—and in Doyle’s case, the insistence on using indigenous, local building materials—enjoyed its heyday from 1945 to 1975, coinciding with Doyle’s most productive period. Maggie always found it an “optimistic” design movement, “reflecting a certain can-do, post-war sensibility” which her father “had in spades.”

Community Work Ethic

Ultimately, it’s not just the architect, but the man they remember with such fondness. “Every Sunday afternoon at church, without fail, the topic of conversation was what are we doing to improve our community?” Maggie recalls.

Roger Bergia, former superintendent of Peoria Heights schools, remembers the honesty, business pragmatism and conservatism of the man who would serve as the district’s architect and, eventually, its school board president. “He wasn’t going to stick you with anything unless you needed it,” he notes.

They remember the sometimes-gruff exterior that hid a softer, perhaps surprisingly forward-thinking side. “He was a force of nature, larger than life. I called him ‘The Zone,’” says Maggie. “He was a terrific teacher… I would characterize him as a ‘leader of men,’ but he hired women well before it was politically correct.”

Finally, they look back at the work ethic of a man who wished to be at his desk until his final moment—who had a yellow legal pad of projects on his lap the day before he died. “In 1968, I was 14, during the Vietnam War. And one day he said to me, ‘Mary Agnes, culture as we know it is dead. So we build.’ That’s how he reacted to the country going up in flames.”

In Peoria Heights, Dick Doyle found a place to spread his wings, as Bill Rutherford did, as Blickenstaff did, as the Vidals hope to do—on the shoulders of those visionaries who came before.